Lucy Catchpole

Tiny Tim is notorious amongst disabled people – short-hand for a certain sentimental disabled character type. I re-read A Christmas Carol recently. I was curious – how bad is Tiny Tim? Was there perhaps something in there I could reclaim?

“he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas-day who made lame beggars walk and blind men see.”

No – I can’t reclaim Tiny Tim as some sort of subversive disabled icon. Unsurprisingly. I did try – the glimpse of his ‘active little crutch’ is a compelling detail.

But Tiny Tim is basically an angel-child. He’s a fantasy idealised disabled child – uncomplaining, selfless, small – utterly unreal. This is the point of him, of course. He’s a dramatic device – literally designed by Dickens to deliver the maximum emotional punch.

So when Scrooge is shown the future, and in this future, Tiny Tim is dead – this is the big emotional moment that truly changes Ebeneezer Scrooge. Not the glimpses of the ex-fiancée he regrets not marrying, nor the ghost of his former business partner with his warnings of a hellish afterlife. Nor the immediate aftermath of his own death – his belongings carelessly picked over and bargained for. No, Tiny Tim is the true catalyst.

And because this is fiction, Scrooge gets to change the future.

So Scrooge buys a massive turkey etc, and as a result… Tiny Tim does not die. It can’t be that simple – but really, in this book, it pretty much is.

What do readers learn from this?

They learn that death can be prevented by kindness and charity – amongst other things. And why does this matter? For many reasons. Partly because it’s often untrue.

Tiny Tim may be unreal, but he was loosely based on a real Victorian disabled boy. Dickens’s own nephew in fact – Harry Burnett.

There are crucial differences. Unlike Tiny Tim, Harry was not impoverished. His uncle was a pretty successful author, after all. They had contacts. Access to medical expertise was not an issue, and they were able to make the lifestyle changes doctors suggested.

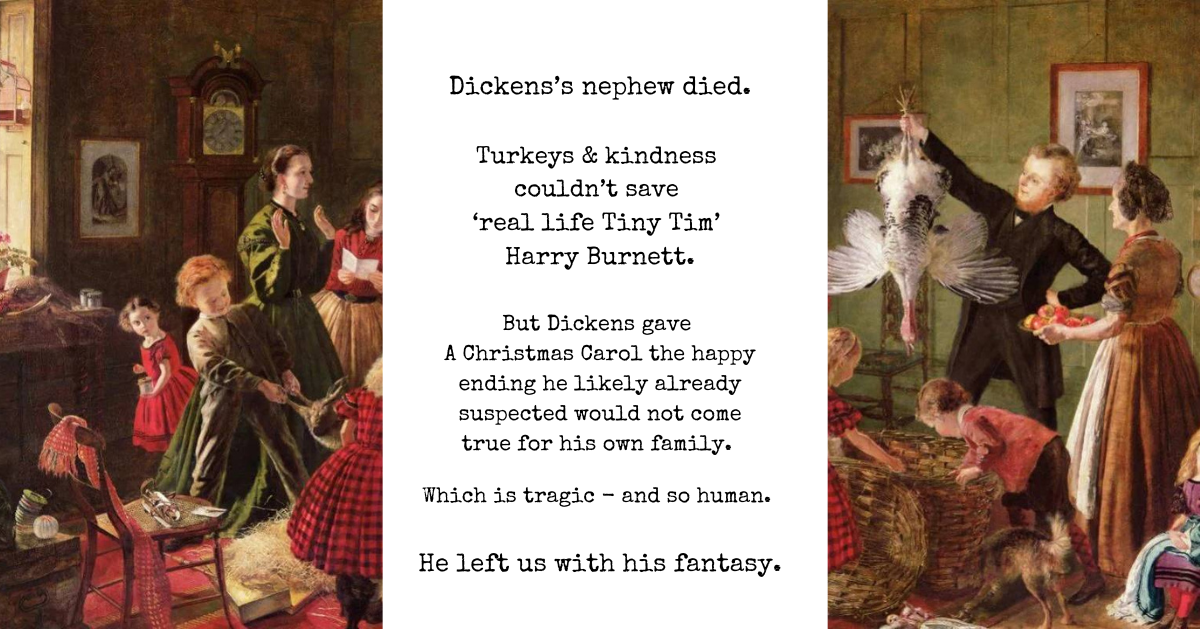

But just a few years after A Christmas Carol was published – Dickens’s nephew died.

The truth is, turkeys and kindness couldn’t save Harry Burnett – the ‘real life Tiny Tim’.

But Dickens gave A Christmas Carol the happy ending he likely already suspected would not come true for his own family. It’s tragic – and so very human.

He left us with his fantasy.

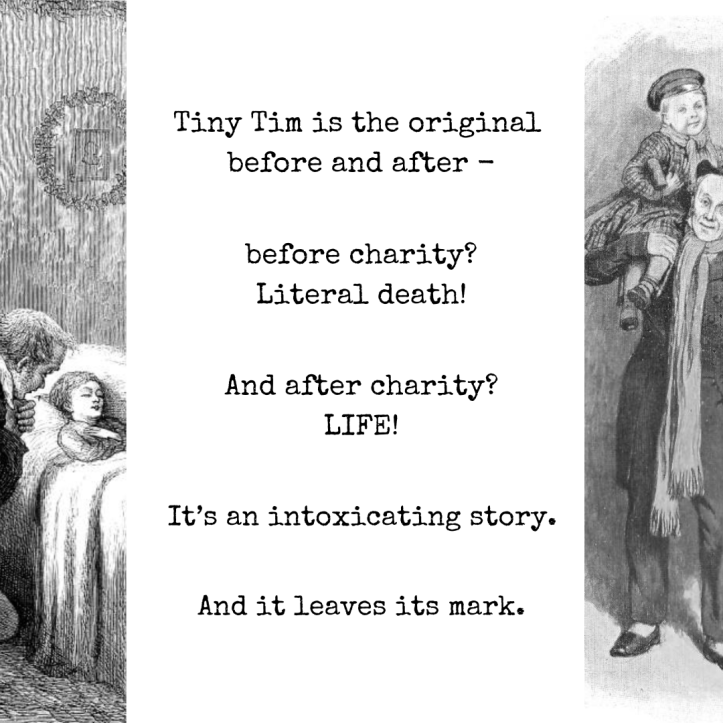

Real life is complicated. That was true both in Victorian London and today. But the story of Tiny Tim is not complicated at all – it’s simple – and that simplicity makes it powerful. Tiny Tim is the original before and after. Before charity? Literal death. And after charity? Life. It’s an intoxicating story. And it has left its mark.

The Victorian response to Dickens’s character was wildly enthusiastic. New hospital wards were named after him. ‘Tiny Tim’ beds were paid for with charitable donations. Charities bearing his name were created. The Queen of Norway even started sending presents annually to disabled children in London hospitals, signed ‘with Tiny Tim’s love’.

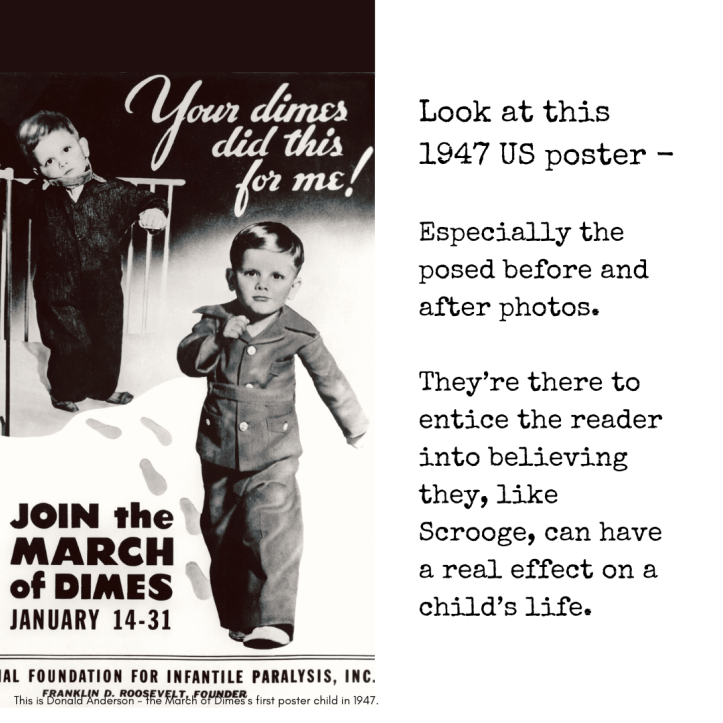

You can draw a direct line through from those original Victorian responses to today. And if that sounds like a reach, look at the 1947 US poster below. Especially the posed before and after photos.

They’re strange, unnatural-looking photos. The very young boy looks almost exactly the same in both to me – I suspect the photos were taken on the same day. In the first, he’s glum, and either propped against, or perhaps tied round the neck (!) to some sort of cot with bars. In the second, he’s striding confidently towards the viewer, in perhaps a quasi-military outfit.

These photos have a purpose – to entice the reader into believing they, like Scrooge, can have a real effect on a child’s life.

But this is not a recent poster. 1947 was a long time ago – surely we’ve moved on?

On this, I don’t think we’ve moved as far as we think.

Here in the UK, Children in Need is marked by millions of schoolchildren every year. As part of their BBC programming they still create before and after videos – disabled children tell the camera just how grateful they are for the viewers’ charity. Slow-motion shots of an ill child pushed in a wheelchair, without hair, cut to a few years later – where the same child is now unrecognisable, and thanks Children in Need for their help.

I decided not to post one on these videos here – it would feel exploitative. But you can find them very, very easily.

Real life is complicated. But these charity stories – like the story A Christmas Carol tells – are simple. Too simple.

I’m not asking anyone to abandon Dickens (or Kermit & Michael Caine, if that’s your bag).

But let’s enjoy it for what it is. Let’s see the Tiny Tim storyline for what it is, and not treat it like some profound truth. Because it really is not that.

And please try not to let Victorian fantasies like Tiny Tim – or the stories modern charities tell – affect how you see real-life disabled people.

I have more to say about these often minor disabled characters in old, classic novels. About the power they have, and the echoes they still leave today. More on Tiny Tim himself, in fact…

But for now – Happy Christmas. From me, and the Muppets.

-Lucy Catchpole

[Image descriptions

1. Can we talk about Tiny Tim?

The caption reads: “Can we talk about Tiny Tim? A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens.”

Underneath, a 1924 black and white illustration by Harold Copping of Tiny Tim, a young boy from Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. He is leaning on a crutch, with a serious expression on his face.

Over the top, a torn fragment of a page with a quote from the novella:

“he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas-day who made lame beggars walk and blind men see.”

2. Can Tiny Tim be reclaimed?

Text reads:

“Tiny Tim is notorious – short-hand for a certain sentimental disabled

character type.

So I thought I’d re-read

A Christmas Carol.

Is Tiny Tim really that bad?

Perhaps I could reclaim him as some sort of subversive disabled icon?”

The illustrations from the first image are partially visible as borders on left and right

3.

Large, central text reads:

“That did not happen.”

Faint quotations from ‘A Christmas Carol’ are around it, including the quote from the first image, and “’God bless us every one!’ said Tiny Tim”.

Illustrations by Fred Barnard from an 1870s edition of A Christmas Carol, – Tiny Tim on his father’s shoulders, holding his crutch aloft – border the text.

4. Text reads:

“Tiny Tim is basically an angel-child.

A fantasy idealised disabled child – uncomplaining, selfless, small –

utterly unreal.

This is the point of him.

He’s a dramatic device – literally designed to deliver the maximum emotional punch.”

Another 1920s illustration by Copping – a very baby-faced, angelic looking Tiny Tim in a hat borders the text.

5. Text:

“So when Scrooge is shown the future…

And in this future,

Tiny Tim is DEAD

this is the big emotional moment that changes Scrooge.

And because this is fiction, Scrooge gets to change the future.”

The borders show a fragment of an 1869 illustration of Tim on his deathbed, by Sol Eytinge.

6. “So Scrooge buys a massive turkey etc, and as a result…”

(In large red text) “TINY TIM DOES NOT DIE”

Illustration: another version of Tim on his father’s shoulders, from 1870 – “Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim,” also by S Eytinge.

7.

“It’s that simple.

(Basically.)”

Colour illustration of Scrooge at his front door, a delivery man is holding an enormous turkey. By C. E. Brock “Scrooge and the Turkey” 1905.

8. What do readers learn?

That death can be prevented

by kindness & charity.

Why does this matter?

Well, for lots of reasons.

Partly because it’s often untrue.”

In the borders, a glimpse of a Victorian colour illustration of the Spirit of Christmas Present, illustrator John Leech 1843.

9. “Did you know Tiny Tim was based on a real Victorian disabled boy?

Dickens’s own nephew, in fact.

Unlike Tiny Tim,

Harry was not impoverished.

But despite all the medical expertise –

just a few years after A Christmas Carol was published…”

Image behind the text, almost translucent, is a contemporary portrait of Dickens’s sister Fanny – the mother of his nephew.

Extremely small text at the bottom reads: “Background portrait – Fanny Burnett, Dickens’s sister, who died before her son.”

10. “Dickens’s nephew died.

Turkeys & kindness couldn’t save ‘real life Tiny Tim’ Harry Burnett.

But Dickens gave A Christmas Carol the happy ending he likely already suspected would not come true for his own family.

Which is tragic – and so human.

He left us with his fantasy.”

Borders – from “The Christmas Hamper,” by Robert Braithwaite Martineau,1850. A Victorian family opening a luxurious hamper, including turkey – an oil painting with rich, warm colours.

11. “Real life is complicated.

That was true in Victorian London and it’s true today.

But the story of Tiny Tim is simple – and REALLY powerful.”

Triangular borders at the side show on the left, a snippet from Charles Green’s 1879 Sunday Afternoon in a Picture Gallery, and the right his Sunday Afternoon in a Afternoon in a Gin Palace.

12. Text reads, “Tiny Tim is the original before and after – before charity? Literal death! And after charity? LIFE! It’s an intoxicating story. And it leaves its mark.”

The left image is the 1869 illustration of Tiny Tim on his deathbed, by Sol Eytinge.

The right image shows smiling Tiny Tim, being carried on his father’s shoulders, in yet another variant, this one by Charles Green in 1905.

13.

“You can draw a straight line from the wildly enthusiastic Victorian response to Tiny Tim

- the new Tiny Tim charities,

- the Queen of Norway sending presents to children in London hospitals signed ‘with Tiny Tim’s love’

to now.

Sounds like a reach?”

In the bottom right hand corner is a small illustration of Tiny Tim holding a cane, with the caption “God Bless Us Every One”, by E. A. Abbey, 1876.

14. March of Dimes before and after charity poster

On the right, my text reads:

“Look at this 1947 US poster –

Especially the posed before and after photos.

They’re there to entice the reader into believing they, like Scrooge, can have a real effect on a child’s life.”

On the left, a vintage 1947 US poster for polio charity March of Dimes, with before and after photos of a very young boy. At the top are the words, “Your dimes did this for me!”

In the before photo, the child has a serious expression and appears to be propped against or even strapped in a standing position to a cot with bars – a strange, uncomfortable, clearly posed image. In the after photo on the right, the same child is carefully dressed and marching confidently, wearing a perhaps quasi-military outfit. The boy looks the same age in the same photo – there is frankly no discernable difference in the two images except in the way the photo has been set up, and his facial expression.. They appear to me to have been taken on the same occasion.

15.

“But that was 1947.

We’ve moved on now – haven’t we?”

16.

“HAVE WE?

Children in Need still have before and after videos.

I won’t put a video of disabled kids up here – but they aren’t hard to find.

This below is a screenshot – just as the ‘before’ becomes the ‘after’.”

The small image below is a tweet screenshot from BBC Children In Need – mid transition, you can see a child sitting from behind without hair, merging with an image of the same boy walking towards the camera, now with brown hair.

17.

“Real life is complicated.

The story A Christmas Carol tells is simple.

Don’t abandon Dickens.

(or Kermit & Michael Caine, if that’s your bag)

But let’s enjoy it for what it is.”

Visible behind is a still from The Muppet Christmas Carol.

18.

“And let’s see the Tiny Tim storyline for what it is, and not treat it like some profound truth.

Because it isn’t”.

The image underneath is an illustration of the Cratchit’s Christmas dinner, by E. A. Abbey in 1976. The image is festive if not opulent – the mother wears a red dress with lace collar.

19.

“And please try not to let Victorian fantasies like Tiny Tim – or the stories modern charities tell – affect how you see real-life disabled people.”

The photo behind is of me – a white wheelchair user with long brown hair, I’m wearing a brown beret, it’s a mirror selfie.

20.

“Happy Christmas!”

Above a still from The Muppet Christmas Carol, 1992 – Miss Piggy, Kermit Senior and Junior in Victorian outfits. It’s like the many Tim-on-father’s-shoulder images we’ve seen – he holds up his crutch. But it’s somehow less annoying when Tim’s a puppet.]

![“Happy Christmas!” Above a still from The Muppet Christmas Carol, 1992 - Miss Piggy, Kermit Senior and Junior in Victorian outfits. It’s like the many Tim-on-father’s-shoulder images we’ve seen - he holds up his crutch. But it’s somehow less annoying when Tim’s a puppet.]](https://thecatchpoles.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/20-happy-christmas-from-the-muppet-christmas-carol.png?w=723)